|

American Beer Month

Hops in their blood

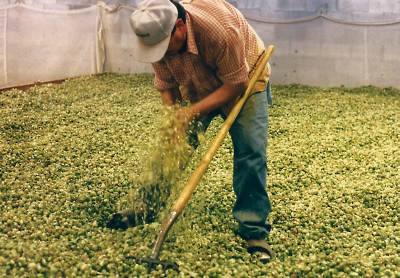

Joe Cardenas "calls the kiln" at a Yakima Valley farm

Thomas Huck was searching for the right words. "There's something unique about hops. If a truckload of apples goes by, nobody looks twice," he said. But if it's a truckload of hops and a few bounce off, "they say, 'That's good for three-four beers right there.' "

Huck works for S.S. Steiner, in Yakima, Wash. The Yakima Valley is the second-largest hop producing region in the world, behind Germany, as well as the leading apple producer and an area rich with vineyards. Fields producing each of the three crops touch at places, but crop rotation isn't an alternative. Trees take time to grow, and a single hop plant will send up vines for 20 years.

Hops arrived in the Yakima Valley in 1868, so many farms are staffed by workers four or five generations into hops.

Kevin Laurent's father and grandfather were in the industry. "I went off to college and I was never going to come back," he said. But it's hard to stay away. He eventually returned to manage two hop ranches for S.S. Steiner in the valley.

Although the way hops are picked, dried and packaged has changed little in 25 years, the industry hasn't stood still. "You can really mess up a hop if you make the wrong decision," Laurent said. "It's changed a lot in the last 10 years, with all the varieties. ... When I was a kid there were two hops - an early and a late Cluster."

Clusters were the dominant hops in the Yakima Valley 20 years ago, for at the time they were both high in alpha acid and hardy. Hops with much higher alpha acid levels (meaning they are more bitter and therefore more economical) have since been developed.

Each hop requires a different measure of care along the way. "You are learning all the time," said Jerry Patnode, 61 and a veteran of 36 years with Steiner. His father had a 20-acre hop farm in nearby Moxee City, and he raised nine children on it.

"I had a wood pail that I had to fill up with hops (during the harvest) before I could go out to play," Patnode said.

Jerry Patnode inspects a bale

|

He is an inspector at Steiner, taking core samples of each bail before it is stored in the warehouse. He quickly learned the differences between each of the varities. One time a rancher accidentally mixed bales of hops before delivering them to Steiner. Some were Cluster and some Galena, but once the hops are packed in 200-pound bales, the difference isn't apparent.

Steiner had each bail analyzed. Meanwhile Pantnode pulled 36 bales of 200 aside that he thought were Cluster and marked the rest as Galena. The analysis prove him right about every single bale.

One thing Patnode is looking for when the bales arrive is how dry the hops are. Those not dry enough are more likely to develop hot spots and present a fire danger. "You learn your growers, some bale hotter," Patnode said.

After they are first harvested, the hops are taken to sheds where they are kilned. Some hops dry more quickly than others, some need to be stored with a little more moisture left in them. They are spread out in the kiln, so air does about 75 percent of the drying.

"Calling the kiln" is an art. Joe Cardenas spends the growing season working with pesticides, then tends a kiln during the harvest. His father, who has worked on the same ranch for 37 years, does the same thing. Joe Cardenas patrols the kiln, stopping first to slap an area with a pitchfork, then maybe stopping to dig his hand deep into the hops. He will pull out a handful and rub the hops vigorously. He may decide to turn over a few forks of hops or move to another area.

How does he know when the hops are dry? "You stick your arm in about this far," he said, illustrating. "If it feels right, they are ready."

Jerry Patnode, who does a different job many miles away, would understand. "Working with hops, it gets in your blood," he said.

July 2000

|